Qui la prima parte dell’intervista.

Andiamo nello specifico del vostro progetto. Fate terminare la linea C a Piramide (separandola dal troncone San Giovanni – Venezia). Perché questa scelta?

Andrea: Ogni progetto, piccolo o grande che sia, deve essere concepito in un percorso progettuale che permette di dimostrare in maniera inequivocabile che la soluzione scelta sia in grado di rispondere alle 4S: sostenibilità tecnica, sostenibilità ambientale, sostenibilità sociale e sostenibilità finanziaria. Non si può prescindere dall’individuazione di una serie di alternative che siano le migliori possibili per almeno uno di questi aspetti e da una loro discussione con tutti i soggetti coinvolti nella gestione, controllo e uso della città: il Comune in tutte le sue sottostrutture, le Soprintendenze archeologiche (che sono amiche e non nemiche della città), gli enti tecnici, non ultimi i cittadini. Il processo concertativo e partecipativo è la chiave per trasformare qualunque idea progettuale in un successo.

La linea C non è nata da un percorso progettuale di questo tipo ma come un assunto, un qualcosa che non si poteva fare che in questo modo. Ad iniziare dal tracciato: e infatti le Amministrazioni che si sono succedute reagivano con irritazione alla richiesta di chiarimenti. Quando non ci sono risposte è difficile rispondere al più spontaneo dei “perché?” se non con un “perché sì!”.

Gli stessi studi trasportistici hanno verificato a posteriori la scelta del percorso San Giovanni-Venezia-corso Vittorio-S. Pietro. Diciamo subito che il giusto percorso progettuale è stato esattamente rovesciato: siccome storicamente si era pensato di trasformare in metropolitana la linea tramviaria che da via Giolitti correva lungo la Casilina sino a Grotte Celoni e Pantano, portandone il capolinea a piazza Venezia si pensò semplicemente di proseguire verso il Centro Rinascimentale. E guardando una mappa qualsiasi del Centro di Roma – oppure, oggi, una visione satellitare – è sembrato subito logico procedere lungo corso Vittorio Emanuele per arrivare a San Pietro attestando il capolinea di volta in volta più in periferia per evitare di ripetere l’errore di avere un capolinea in piena area urbana (come fu Ottaviano con la linea A).

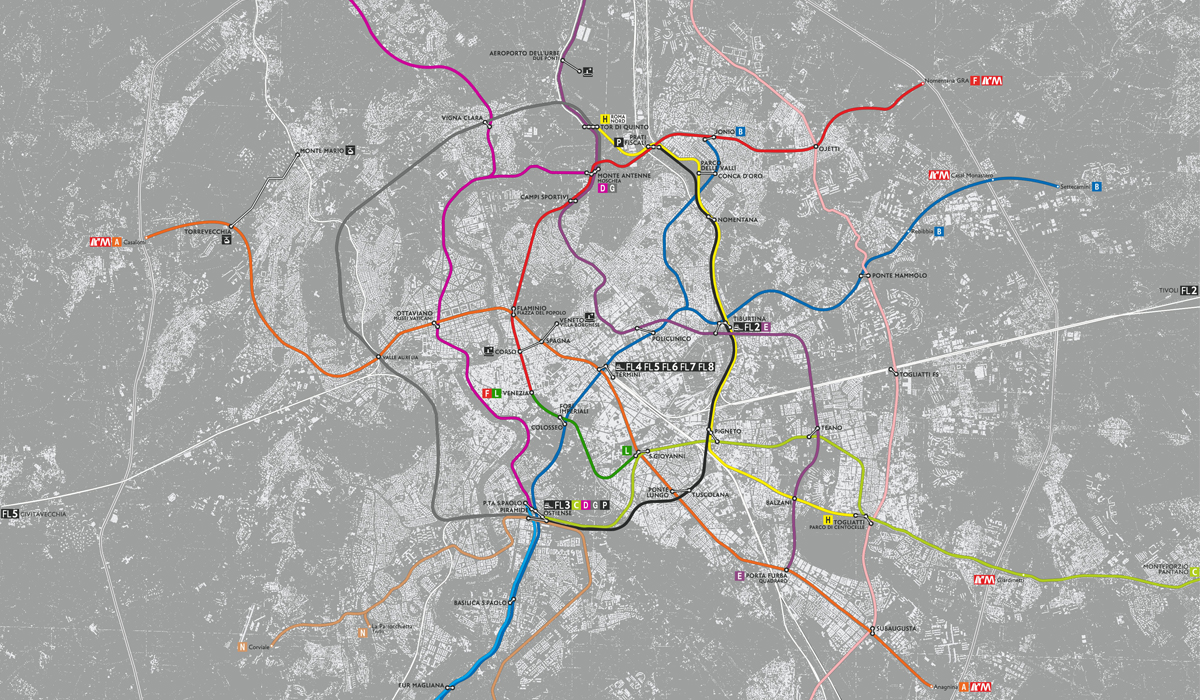

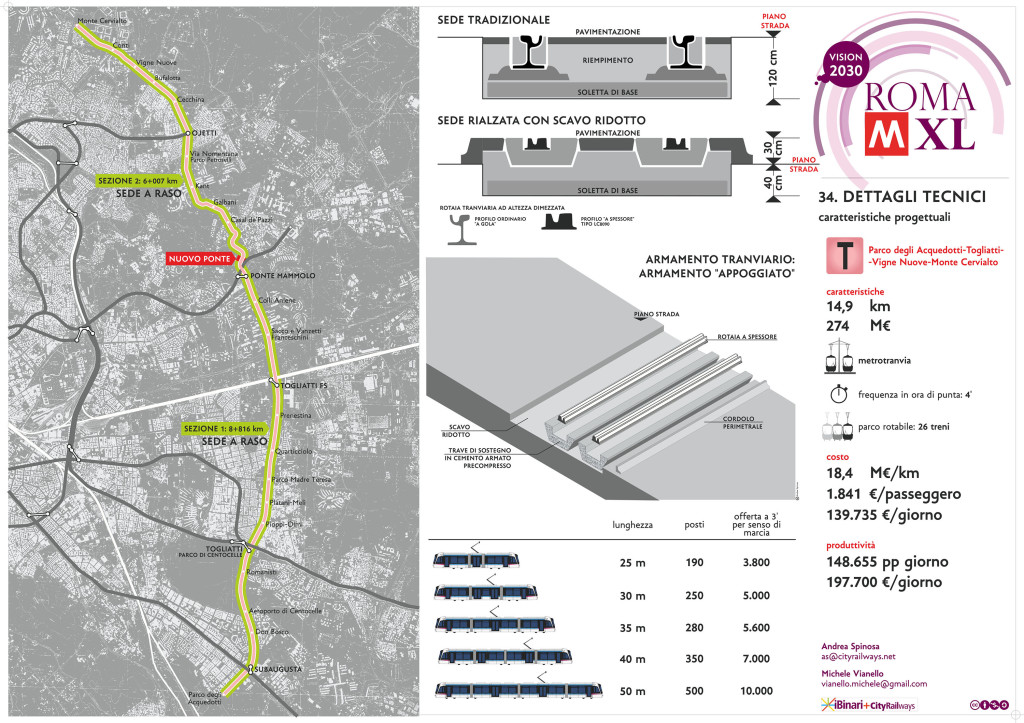

Per questo abbiamo voluto azzerare ogni preconcetto, individuando una gamma di alternative possibili – sempre verificandone le 4S – per la continuazione oltre San Giovanni. È emerso che l’intervento con la maggiore produttività in termini di passeggeri ( e quindi al rapporto benefici/costi per ogni euro speso) è proprio l’attestazione al nodo incompleto di Ostiense-Piramide dove già passano una metropolitana, una semi-metropolitana (la Roma-Lido), l’anello ferroviario e la dorsale tranviaria più importante della città.

Il troncone San Giovanni-Venezia resta nella proposta solo perché l’iter realizzativo è già approvato. Attestarsi a Venezia costa 900 milioni di € per un guadagno di 190mila passeggeri giornalieri trasportati rispetto all’attestamento a San Giovanni: 4.736 euro per passeggero. Attestarsi a Piramide costerebbe 600 milioni di € per un guadagno di 220mila passeggeri giorno che avrebbero grazie alla linea B e al tram 3 comunque la possibilità di raggiungere via dei Fori Imperiali e quindi piazza Venezia. Ma ad un costo di 2.730 euro per passeggero. Il 42% di costo unitario in meno ed una migliore funzionalità di rete, per noi, giustificano più di una riflessione.

Michele: Come spiega Andrea abbiamo cercato di spazzare via tutti gli strati accumulati dai progetti precedenti. La linea C, nella nostra versione, ha una giustificazione di efficienza, fattibilità e realismo, ma apre anche a una vera strategia di policentrismo per la città. Le centralità del piano regolatore come Massimina o Madonnetta non hanno la forza di attrazione necessaria per esistere senza centralità metropolitane diverse dal Centro Storico a una distanza intermedia. Una grande infrastrutturazione del nodo di Ostiense prefigura e auspica un nuovo ruolo di mediazione nella regione urbana. Naturalmente molte condizioni potrebbero cambiare per una piena realizzazione di questa idea: un aumento del traffico interregionale e nazionale su quella stazione, di cui il TAV Italo rappresenta un primo esempio, ma anche una vera trasformazione delle aree intorno (magari anche smart e sostenibile), come le ex-Italgas. Come vedi è una rete che prefigura per lo meno le condizioni per una diversa città futura.

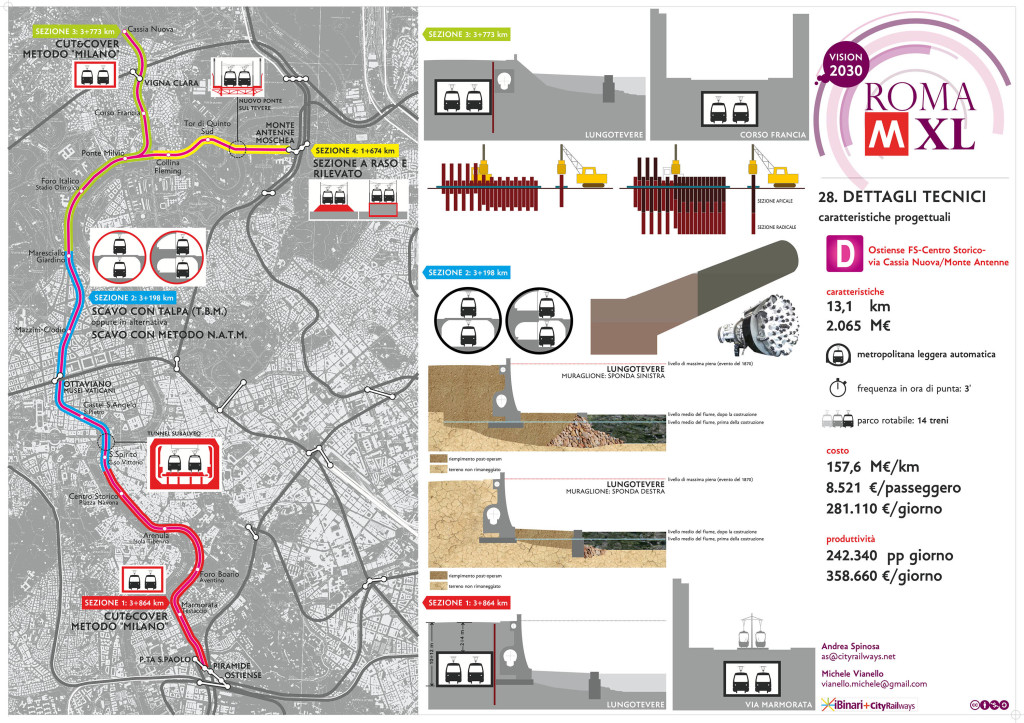

La linea forse più interessante è la D, che da Piramide (che diventerebbe un nodo di scambio fondamentale) attraversa il centro della città (Piazza Navona, Castel Sant’Angelo, ecc.) arrivando poi con una diramazione sulla Cassia e con un’altra a Monte Antenne. Parlateci di questa linea.

A: È la più importante del sistema soprattutto nella tratta che corre sotto il lungotevere orientale sino al quartiere Prati. È quella più importante sia per rilanciare la città come prodotto turistico sia per restituire agli abitanti il cuore della propria città. Con i lungotevere ridotti a mere arterie di scorrimento non solo si è perso il contatto con il fiume – elemento generatore della città – ma si è lasciato morire tutto il tessuto urbano adiacente. Persino i turisti hanno rinunciato a passeggiare sotto i platani e chi lo fa, vive un senso di straniamento e stordimento: una città che perde i propri simboli è una città che sta morendo.

M: La linea D è forse la più emblematica dell’approccio che abbiamo tenuto. Quando si è posto il problema di come servire il centro siamo partiti da quella che abbiamo chiamato una mappa della “trasformabilità”. Con i dati disponibili sui ritrovamenti archeologici, la morfologia della città storica, etc. ci siamo chiesti lungo quali direttrici si potesse far passare la sezione di una metropolitana. I lungoteveri rappresentavano una delle opzioni più facili, essendo riempiti da terreno di riporto come dimostrano le fotografie e i disegni di progetto degli anni ’90 del 1800. Le caratteristiche di Roma come luogo di antropizzazione storica sono state parte della definizione del problema e non qualcosa con cui fare i conti in un secondo momento, con operazioni di facciata, come l’idea di stazioni-museo a Piazza Argentina e Chiesa Nuova su cui la Sopraintendenza ha naturalmente posto il veto. I tracciati proposti non sono necessariamente definitivi. Lo stesso Andrea ha da poco elaborato una proposta molto interessante per portare la linea C a Ostiense secondo un tracciato leggermente diverso. L’aspetto principale è marcare una differenza culturale e proporre un approccio fresco nell’affrontare problemi complessi.

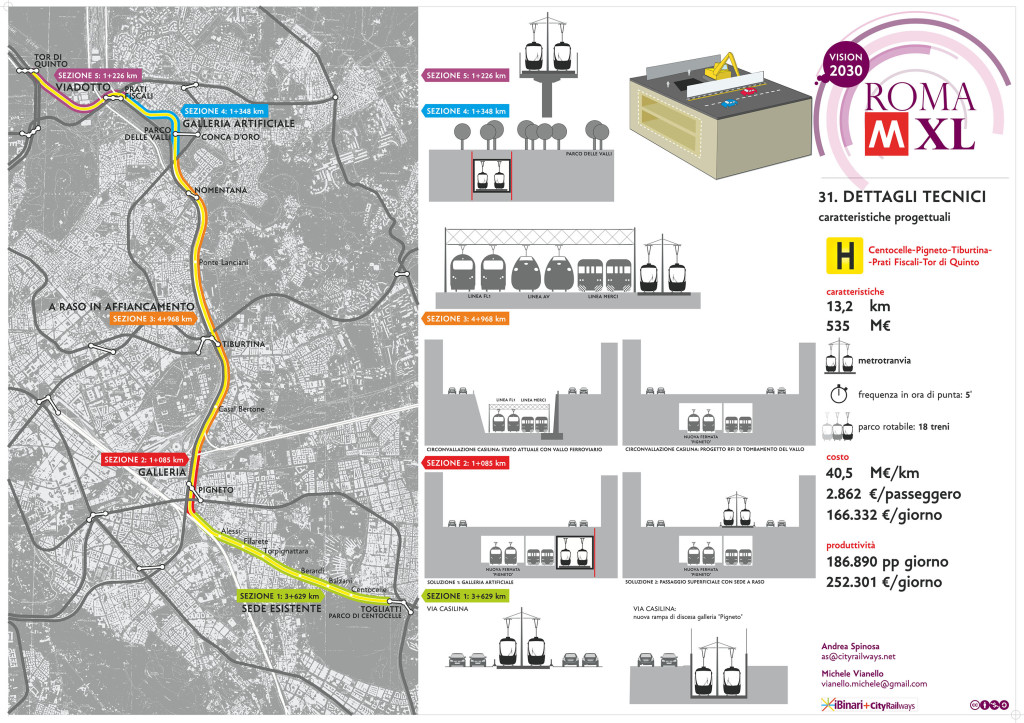

Altra idea intrigante è la linea H, che da Centocelle arriva a Tor di Quinto, ricalcando il percorso della tangenziale interna. Pensate che attraverso questa linea sia possibile diminuire il traffico privato che insiste in questo tratto?

A: In tempi di crisi – ma dovrebbe essere sempre vero – è necessario investire quanto si ha, rinnovando, trasformando e potenziando. È una logica mai adottata a Roma: si pensi che, pur in quadro di cronica penuria, ogni metropolitana ha sostituito infrastrutture preesistenti che sono state smantellate di tutto punto, come fossero vestiti dismessi. La linea A ha “mangiato” quanto restava delle tramvie dei Castelli; la linea C ha mangiato la ferrovia “Roma-Pantano”. Si dismette, non si integra né si recupera. Non ci sembra un atteggiamento molto sensato, soprattutto se si riflette sul fatto che delle carrozze ferrotramviarie, se accuratamente mantenute, possono avere una vita di servizio di 50-70 anni mantenendo un’affidabilità molto elevata. Questo accade a Berlino con la metropolitana ma anche in molte città tedesche e in tutto l’Est europeo con reti tramviarie centenarie perfettamente funzionanti.

La linea H nasce dall’aver studiato gli spostamenti giornalieri di un quartiere che si è profondamente trasformato in questi anni, passando da area degradata a centro di una nuova Roma multietnica. Molte persone straniere sono andate a vivere lì perché la degradazione manteneva bassi gli affitti e rendeva disponibili locali per attività artigianali e commerciali. La ferrovia Roma-Pantano garantiva i collegamenti con il centro, mentre la linea 409 con le metropolitane A e B. Conoscendo la volontà dell’Amministrazione di degradare la ferrovia a semplice tramvia ci siamo chiesti quali sono i tragitti giornalieri percorsi da queste persone e se fosse possibile trasformare un residuo ferroviarie in un’opportunità. Tor Pignattara, Pigneto, la nuova stazione Tiburtina, Salario, Prati Fiscali, Nomentano sono tutti elementi della città Novecentesca che dipendono relativamente dal Centro Storico: perché insistere ancora con una logica centro-dipendente?

Offrire nuove connessioni crea nuovi modi di trasporto e nuove opportunità: non sono solo le aree consolidate ad offrire servizi o posti di lavoro. Se si fanno funzionare aree degradate si crea l’opportunità perché sia il lavoro a ripresentarsi in queste aree. Se si riducono gli spostamenti pendolari di lungo raggio si riduce il traffico: ecco un esempio di come operare con il trasporto pubblico per rendere più “smart” una città.

M: Abbiamo questa convinzione. La tangenziale interna è parte della città. La sua rimodellazione, tra cui l’abbattimento di alcuni tratti in sopraelevazione, può passare anche da una sinergia con il trasporto pubblico, magari del tipo park and ride.

Dimostrate una grande attenzione nei confronti delle periferie. Con la linea T, ad esempio, queste vengono unite e collegate, con diversi nodi di scambio, al centro della città. Una tratta radiale come questa pensate possa assottigliare la sensazione di lontananza di questi territori e far diminuire il numero di auto che accedono alla parte centrale della città?

A: Roma è una città a bassa densità: entro i 360 km quadrati interni al raccordo, vivono circa 2,1 milioni di persone. Parigi nella stessa area concentra 6,7 milioni di persone. Monterotondo, Mentana, Guidonia, Tivoli, i Castelli almeno sino ad Albano, Pomezia, Anzio e Nettuno sono a tutti gli effetti quartieri di Roma. È un’area di 3.500 km quadrati che conta 3,5 milioni di persone. La sterminata banlieue parigina non è poi così sterminata: si estende per 3.600 kmq e conta 11 milioni di persone. Madrid, altra città molto simile a Roma come struttura, si estende su una superficie di 2.400 kmq con una popolazione di 6,2 milioni di persone. Pochi esempi per dire che Roma non è una grande città in termini di popolazione ma è una delle più grandi città del mondo per estensione superficiale. Un mix profondamente negativo e costoso perché costringe un numero relativamente basso di persone a spostarsi su tragitti molto lunghi. La sensazione estraniante di essere comunque “distanti” provata da chi vive in periferia è quindi una certezza.

Alla forza centrifuga del mercato edilizio (e della speculazione) che ha proiettato lontano (oltre il Grande Raccordo Anulare) il 40% della popolazione dell’area urbana ci si oppone in un solo modo. Realizzando delle linee di trasporto tangenziali che uniscano le periferie più interne e le mettano in condizione di non essere più lontane. Allo stesso tempo che rendano le periferie più esterne meno (per quanto possibile) remote.

M: Come ho anticipato all’inizio in modo indiretto, uno degli obiettivi era anche quello di creare una rete inclusiva che accogliesse i problemi sociali e spaziali della dispersione senza glorificarli o accettarli passivamente. Abbiamo quindi fatto in modo che la rete avesse caratteristiche isotrope (cioè uguali – o almeno simili – in ogni direzione). Con diversi adattamenti al contesto, si è cercato di mantenere questa filosofia. Caratteristiche simili significano anche accessibilità simile. Risolvere il problema del traffico nel tipo di urbanizzazione che caratterizza Roma, un territorio vasto a densità relativamente bassa, non è semplice. Una maglia larga e relativamente omogenea, ma con sezioni diverse, sembra sostenere in modo adeguato le proiezioni.

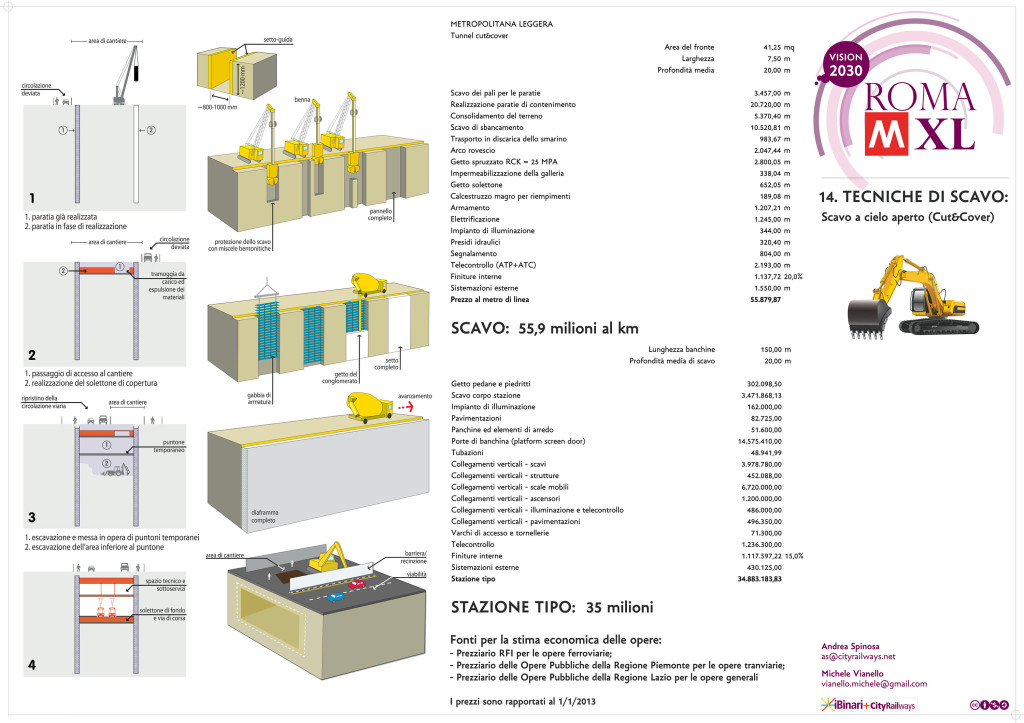

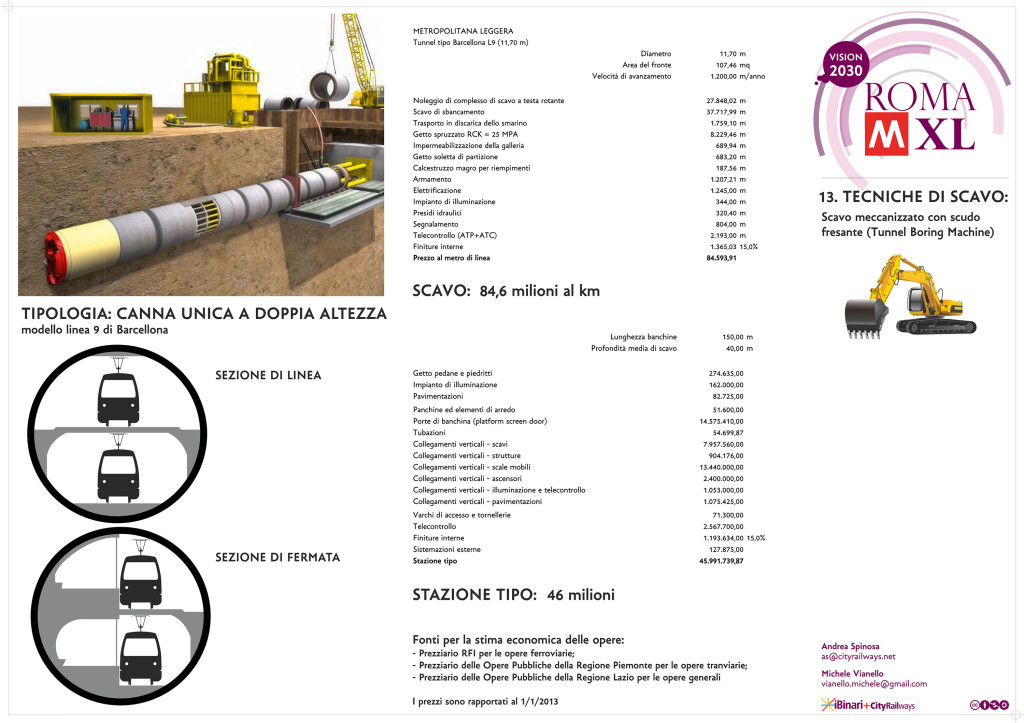

Spiegate molto bene i processi di scavo e i metodi costruttivi. Come si supera, in una città come Roma, il problema dell’archeologia e della costruzione nel sottosuolo?

A: Per prima cosa mettendo in collaborazione i progettisti con i tecnici della Soprintendenza. Troppo spesso gli ingegneri esperti in “tunnelling” non conoscono la “Forma Urbis” né sanno leggere una moderna Carta Archeologica e troppo spesso gli archeologici tra i più preparati del mondo, chiamati a vegliare sul patrimonio storico più ricco del mondo, si affidano più ai preconcetti che alle equazioni della fisica in termini di vibrazioni e inquinamento, per esempio.

Le motivazioni con cui si è giustificata la rinuncia alla stazione “Nomentana” della B1 piuttosto che i problemi tecnici che si sono dovuti affrontare nelle poche stazioni in galleria della linea C sinora realizzate vengono trattati più come fossero verità misticamente assiomatiche che con semplice e sana schiettezza ingegneristica.

Roma non è un luogo facile per le metropolitane ma non è il caso di ricorrere ai superlativi: a San Francisco negli anni Settanta per il BART si è operato in terreni fortemente cedevoli, saturi di acqua marina. A Los Angeles le gallerie della metropolitane sono state realizzate con una doppia camicia esterna per essere sicure anche in caso di sisma superiore al grado M7 (lo stesso che distrusse Messina e Reggio Calabria nel 1908). A Parigi nel primo Novecento sono state individuate soluzioni innovative per evitare che i gli allora fisiologici cedimenti durante gli scavi delle gallerie più profonde potessero ripercuotersi su edifici se non millenari come quelli di Roma, di forte valenza storica e culturale.

Ancora una volta bisogna prima smontare i preconcetti che appesantiscono il dibattito romano, mettere le risorse, che pure ci sono, in condizioni di lavorare al meglio. Solo allora si potrà ragionare sulle soluzioni tecniche di volta in volta più idonee: dallo scavo con la classica talpa, a quello sempre a foro cieco ma con macchine escavatrici alle gallerie scavate dall’alto con la tecnologia del cut&cover (taglia e copri).

M: La risposta di Andrea mi sembra esauriente. Le considerazioni fatte per la linea D hanno comunque validità generale.

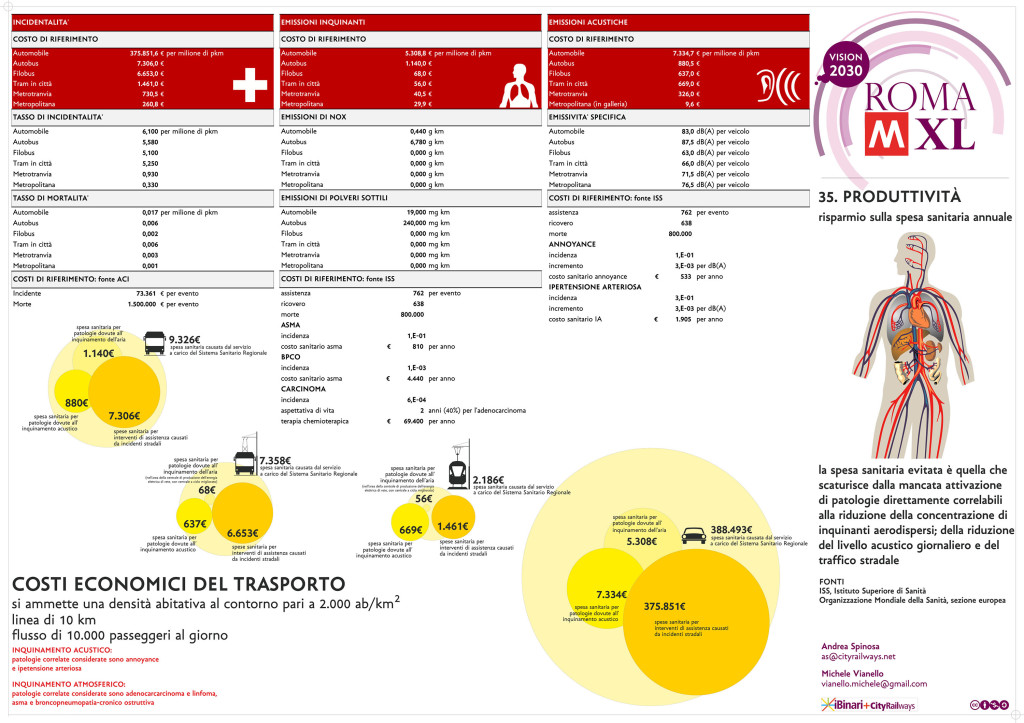

Alla fine del vostro lavoro parlate del risparmio sulla spesa sanitaria annuale. Un dato che di solito non viene tenuto in grossa considerazione, nonostante la sua importanza. Quanto influisce la presenza di una rete di metropolitane sul benessere e la salvaguardia della popolazione?

A: In ottobre lo IARC, l’Istituto Internazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro – dell’Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità – ha inserito il prodotti di scarto della combustione dei motori diesel tra i carcinogeni di livello 1, ovvero quelli per i quali è certo il nesso causa-effetto. Si tratta di una decisione senza precedenti alla quale non è stato dato il rilievo dovuto: non è difficile immaginarne i motivi.

Il Centro di Ricerca danese sul Cancro, ha seguito per 13 anni una popolazione sparsa per tutta Europa di 313mila persone (fra le quali anche quelle seguite da ricercatori italiani a Roma e a Torino), individuando un chiaro nesso fra esposizione a polveri e tumore al polmone. In particolare nella forma che colpisce anche i non fumatori (adenocarcinoma). I ricercatori sono riusciti a mettere in relazione i 2.095 casi di tumore al polmone insorti nel campione di studio nel periodo considerato con il livello di polveri nella zona di residenza dei malati, riuscendo ad apportare le correzioni per potenziali effetti interferenti come il fumo, la dieta e il tipo di occupazione. Si è constato che a ogni incremento di 5 μg per metro cubo di PM2.5 il rischio di tumore al polmone aumenta del 18%, e del 22% a ogni aumento di 10 μg/mc di PM10. Più le polveri sono sottili, insomma, più sono nocive.

Sempre l’anno scorso un team internazionale guidato dal prof. Mills dell’Università di Edimburgo ha confermato un altro effetto dell’inquinamento urbano sui ricoveri e la mortalità da scompenso cardiocircolatorio. Mettendo insieme i dati provenienti da 12 diversi Paesi, i ricercatori hanno potuto riscontrare un chiaro nesso causale fra l’aumento della concentrazione degli inquinanti nell’aria e il subitaneo aggravarsi dello scompenso, addirittura nel giorno stesso della massima esposizione. Il rischio di finire in ospedale per una crisi di insufficienza cardiaca o di morirne cresce del 3,5% all’aumentare di 1 parte su un milione di monossido di carbonio, del 2,3% all’aumento di 10 parti per miliardo di biossido di zolfo, dell’1,7% per uno stesso aumento di biossido di azoto e di circa il 2% per ogni incremento di 10 μg/mc di polveri. Le polveri sottili, passando dai polmoni nel circolo sanguigno, sono in grado di provocare una infiammazione generalizzata che facilita la formazione di placche aterosclerotiche, trombi e ischemie. Dall’altro lo stress chimico determinato dalle particelle inquinanti agisce anche sul sistema nervoso autonomo (simpatico e parasimpatico) determinando aritmia e danni progressivi a cuore e coronarie.

Altri studi hanno dimostrato in maniera limpida la correlazione tra inquinamento e patologie dell’apparato respiratorio (broncopneumopatie, asma infantile) così come incidenza neoplastica (in particolare leucemie e mielomi) a prescindere da predisposizione genetica o comportamenti personali. Quello che colpisce di più è l’avanzamento di queste patologie verso le fasce più giovani e i bambini.

M: Naturalmente sottoscrivo a pieno quello che dice Andrea: influisce moltissimo. Occorre però tenere a mente che un sistema di trasporto pubblico di massa e la sua corretta gestione finanziaria non risolve di colpo gli enormi problemi e ritardi della Sanità regionale. Può comunque aiutare e dare l’esempio su come gestire fondi, e l’idea semplice di includere nel calcolo le future esternalità negative sulla salute che si andrebbero ad evitare è scientificamente molto innovativa. Le strategie di investimento sulla sanità a lungo termine potrebbero assolutamente includere scelte di questo tipo. Sappiamo anche però quali grumi di potere si toccano nel pensare a una razionalizzazione delle spese sanitarie. Indicare questa via è l’inizio di un percorso che è naturalmente molto complesso.

Se vi dessero l’opportunità di realizzare solo alcune delle linee da voi ipotizzate (magari per motivi economici o politici), a quale dareste la priorità? Oppure verrebbe meno l’effetto rete che rende questo progetto qualcosa di necessario per Roma?

A: Il Piano è pensato per essere realizzato per sezioni, utilizzando parte dei benefici apportati man mano che si procede con l’esercizio delle nuove linee come volano per avanzare nel completamento. Come detto, la D è la linea più importante per rilanciare la città. Ma è anche quella tecnicamente ed economicamente più onerosa. In termini di contenimento della spesa e massimizzazione degli effetti la linea più interessante è la F con la trasformazione della ferrovia Roma-Nord, un infrastruttura tanto strategica quanto sottoutilizzata. La F, correndo lungo via dei Prati Fiscali, permetterebbe di incrementare la produttività della diramazione B1 indirizzandovi i flussi di uno dei quadranti più popolosi di Roma. Si pensi che dei 225mila passeggeri giorno che si originano da Montesacro e Nomentano la linea B1 riesce a captarne 55mila. Se il carico fosse stato questo, meglio sarebbe stato realizzare un tram per piazza Bologna, senza necessità di ricorrere ad una metropolitana.

M: L’intera struttura della rete è pensata per avere la possibilità di riutilizzare infrastrutture esistenti ed essere costruita per parti. Completare la linea C fino a Ostiense è il primo passo necessario. Andrea sogna più in grande di me, ma io credo che già questo significherebbe un cambio di passo epocale, oltre alla risoluzione di un problema logistico e finanziario che rischia di zavorrare la città per decenni. Mi sembra che sia già molto in cui sperare. Se questa idea, che appare semplice, farà breccia nella mente di chi amministra si può cominciare a discutere seriamente del resto.

Per concludere: c’è un minimo spiraglio che l’idea diventi realtà o che almeno sia l’inizio di una seria discussione sul tema?

A: Roma MXL è stata concepita con metodo scientifico: il nostro obiettivo era quello di partire da una tesi dimostrandone la veridicità in base ad una serie di dati di partenza con un percorso misurabile, ripetibile e controllabile. Investire 1.000 euro nel giusto trasporto pubblico crea un controvalore reale e tangibile di 1.175 euro: un valore minimo pari a 175 euro di guadagno disponibile per la città. Per noi avrebbe il valore di un Nobel, se l’Amministrazione facesse suo questo approccio e lo utilizzasse per aprisse i lavori di un Piano Regolatore del Trasporto di Massa con degli obiettivi chiari e raggiungibili – perché rispettosi delle 4S – già nei prossimi 5 anni.

Qui il link per scaricare ROMA MXL.

[divider]ENGLISH VERSION[/divider]

Let’s go into the specifics of your project. The C line finishes in Piramide station (separating it from the San Giovanni – Venezia stump). Why this choice?

Andrea: Every project, small or large it is, must be designed in a planning process that enables you to demonstrate, unequivocally, that the solution you choose meets the 4S: technical sustainability, environmental sustainability, social sustainability and financial sustainability. We cannot disregard the identification of several alternatives that are the best possible for at least one of these aspects, and a discussion about them with all parties involved in the management, control and use of the city such as the Commune in all its substructures, the archaeological Superintendence (which are friends and not enemies of the city), the technical authorities, and last but not least, the citizens. Harmony and participation are the keys to turn any idea into a successful project.

The C line was not born from a design process of this type, but as an assumption, as something that you could not do but in this way. Starting from the racetrack. In fact, the succeeding Administrations reacted with irritation to the request for clarification. When there are no answers, it is difficult to answer to the most spontaneous “why?” with a “why yes!”

The same studies about transport verified, a posteriori, the choice of the route San Giovanni – Venezia – Corso Vittorio – S. Pietro. Let’s say that the right design path has been exactly reversed. Because historically the tramline that from Via Giolitti ran along Via Casilina until Grotte Celoni and Pantano was thought to be transformed into an underground line, with moving the terminus to piazza Venezia, they just thought to continue until the Renaissance City Center. And looking at any map of the Centre of Rome – or, today, a satellite view – it seemed logical to proceed along Corso Vittorio Emanuele to get to San Pietro, lining up the terminal from time to time in the suburbs, to avoid repeating the mistake of having a terminal in the middle of a urban area (as it was with Ottaviano’s A line).

That is why we wanted to reset all preconceptions, identifying a range of possible alternatives – always checking the 4S – to the continuation beyond San Giovanni. It came to light that the intervention with the highest productivity in terms of passengers (and therefore to the benefits/costs per euro spent) is precisely the lining up to the incomplete hub of Ostiense – Piramide, where there already pass a subway line, a semi-underground line (Roma – Lido), the ring rail and the most important backbone tramline of the city.

The section of San Giovanni – Venezia remains in the proposal only because the realization process has already been approved. Settling in Venezia costs € 900 million for a gain of 190 thousand passengers daily transported, compared to the San Giovanni settling: 4,736 Euros per passenger. Settling at Piramide would cost € 600 million to a gain of 220 thousand passengers a day, that however would have, thanks to the B line and to the tram 3 line, the chance to get Via dei Fori Imperiali and then Piazza Venezia, but with a cost of € 2,730 per passenger. In our opinion, the 42% of unit cost less and a better networking capability, justify more than a reflection.

Michele: As Andrea explained, we tried to sweep away all the layers accumulated from the previous projects. The C line, in our version, has a justification of efficiency, feasibility and realism, but it also opens a real polycentric strategy for city. The centralities of the master plan, such as Massimina or Madonnetta, don’t have the force of attraction needed to exist, without metropolitan centralities different from the Historic Center, to an intermediate distance. A large infrastructurization of the Ostiense’s hub anticipates and hopes for a new role of mediation in the urban region. Of course, many conditions may change to a full realization of this idea: an increase in inter-regional and national traffic on that station, of which the TAV line Italo is a former example, but also a real transformation (maybe, even smart and sustainable) of the surrounding areas, as the ex-Italgas. As you can see, it is a network that foreshadows at least the conditions for a different future city.

Perhaps, the most interesting line is the D line, which from Piramide (that would become a fundamental exchange hub) through the center of the city (Piazza Navona, Castel Sant’Angelo, etc.) would arrive, with a branch, on the Via Cassia, and with another to Monte Antenne. Tell us about this line.

A: It is the most important part of the system, especially in trafficking that runs under the eastern Tiber up to the Prati district. It is the most important, both to revive the city as a tourist product and to give back, to the people, the heart of their city. With the Tiber front reduced to mere arterial roads, we not only have lost the touch with the river – the generating element of the city – but we left to die all the adjacent urban fabric. Even the tourists gave up a walk under the plane trees, and who does it, lives a sense of alienation and stunning. A city that looses its symbols is a city that is dying.

M: The D line is perhaps the most emblematic of the approach we kept. When appeared the problem of how to serve the city center, we started from what we have called a map of the “convertibility “. With the available data on archaeological findings, the morphology of the historic city, etc., we wondered along which lines could it pass a section of a subway. The Tiber fronts represented one of the easiest options, being filled with backfill, as shown by the photographs and design drawings of the 90s in 1800. The characteristics of Rome, as a place of historic anthropology, have been part of the definition of the problem and not something to be reckoned with at a later time, with window-dressing, like the idea of railway museums in Piazza Argentina and Chiesa Nuova on which the Superintendence, of course, has vetoed. The routes proposed are not necessarily definitive. Andrea, he recently has developed a very interesting proposal; to bring the line C to Ostiense according to a slightly different route. The main aspect is to mark a cultural difference and to propose a fresh approach in dealing with complex problems.

Another intriguing idea is the H line, which from Centocelle arrives to Tor di Quinto, tracing the path of the inner ring road. Do you think that through this line would it be possible to reduce the private traffic that insists on this stretch?

A: In times of crisis – but it should always be true – you need to invest what you have, renewing, transforming and strengthening. This logic has never been adopted in Rome. Just think that, even in the context of chronic shortage, every subway has replaced existing infrastructures that have been dismantled at all points, as if they were abandoned clothes. The A line “ate” the remains of the Castelli’s tramways; the C line ate the railroad “Rome – Pantano”. We retire, we don’t complement nor recover. We don’t think this is a very sensible attitude, especially if you reflect on the fact that rail and tram carriages, if carefully maintained, could have a service life of 50-70 years, while maintaining a very high reliability. This is what happens whit Berlin’s subway but also in many other German cities and throughout Eastern Europe, with centuries old tram networks in perfect working order.

The H line comes from having studied the daily movements of a neighborhood that has profoundly transformed in recent years, passing from a degraded area to the center of a new multi-ethnic Rome. Many foreign people went to live there, because the degradation kept rents low and made available locals to craft and commercial activities. The railway Rome – Pantano guaranteed connections with the center, while the line 409 with the subways A and B lines. Knowing the will of the Administration to downgrade the railroad to a simple tramway, we wondered what the daily commuting routes covered by these people are and if it were possible to transform a railway residue into an opportunity. Torpignattara, Pigneto, the new Tiburtina station, Salario, Prati Fiscali, Nomentano are all elements of Twentieth-century city that depend on, relatively, from the Historical Center. Why insisting again with a center subordinate logic?

Offering new connections creates new ways of transport and new opportunities. Not only the consolidate areas can offer services or jobs. If you can run degraded areas, you create opportunity for the job to recur in these areas. If you reduce commuting long range, you reduce the traffic. Here is an example of how to work with public transport to make a city “smarter”.

M: We have this belief. The inner ring road is part of the city. Its remodeling, including the knocking down of some parts in elevation, it could also pass from a synergy with public transport, maybe the kind of park and ride.

You demonstrate a great attention towards the suburbs. With the T line, for example, they are united and connected with several interchanges, in the center of the city. Do you think that a radial section like this could thin the feeling of remoteness of these areas and decrease the number of cars entering the central part of the city?

A: Rome is a city with low density. Within 360 square kilometers of the ring road there are about 2.1 million people. In the same area, Paris concentrates 6.7 million people. Monterotondo, Mentana, Guidonia, Tivoli, Castelli at least until Albano, Pomezia, Anzio and Nettuno are quarters of Rome, as a matter of fact. This is an area of 3,500 square kilometers, which has 3.5 million people. The vast Parisian banlieue is not so vast: it covers 3,600 square kilometers and has a population of 11 million people. Madrid, another city with a structure very similar to Rome’s, covers an area of 2,400 square kilometers with a population of 6.2 million people. Just a few examples to say that Rome is not a big city in terms of population. However, it is one of the largest cities in the world for superficial extension. This is a mix deeply negative and costly, because it forces a relatively small number of people to move on very long routes. The alienating feeling of still being “distant”, experienced by those living in the suburbs, is therefore a certainty.

There is only one way to oppose the centrifugal force of the building market (and of speculation) that projected far (over the Roman Ring Road) the 40% of the population of the urban area; realizing highways lines that join the inner suburbs, and that put them in the condition of not being far away. At the same time, rendering the outer peripheries less (as possible) remote.

M: As I mentioned before indirectly, one of the aim was also to create an inclusive network that could receive social and spatial problems of dispersion without exalting or accepting them passively. So we made sure that the network had isotropic characteristics (i.e. identical – or at least similar – in each direction). With different adaptations to the context, we tried to maintain this philosophy. Similar characteristics mean also similar accessibility. It is not easy to solve the problem of traffic in the kind of urbanization that characterize Rome, an extended area with relatively low density. A wide and relatively homogeneous mesh, but with different sections, seems to support adequately the projections.

You explain very well the excavation processes and the constructive procedure. How is it possible to overcome, in a city as Rome, the problem of archaeology and construction in the subsoil?

A: First putting in collaboration designers together with superintendent. Too often engineer expert in “tunnelling” do not know the “Forma Urbis” nor know how to read a modern Archaeological Map and too often archaeologists among the best prepared in the world, summoned to watch over the richest historical capital in the world, entrust preconceptions more than physical equations in terms of vibrations and pollution, for example.

The reasons with which they justified the renouncement of the station “Nomentana” of B1, or the technical problems that had to be dealt with in the few stations in gallery of C line realized until now, are treated more as if they are mystical truth rather than with simple and healthy ingegneristic sincerity.

Rome is not an easy place for metros, but it is not necessary to resort to superlatives: in San Francisco in the seventies for the BART they worked on highly loose soils, saturated of sea water. In Los Angeles the galleries of the subways were made with a double plaster bound to be safe even in case of an earthquake superior to the degree M7 (the same that destroyed Messina and Reggio Calabria in 1908). In Paris in the early twentieth century have been identified innovative solutions to prevent that the physiological sinking during the excavation of the deepest tunnel could affect the millennial buildings as those in Rome, with a strong historical and cultural value.

Once again it’s necessary first to demolish preconceptions that burden the Roman debate, to put resources, that do exists, in condition to work the best they can. Only than we could think of technical solutions from time to time more appropriate: from the excavation with the classical mole, to that with a blind hole but with the excavators, to the tunnel excavated from high on with the cut&cover technology.

M: I think that Andrea’s response is exhaustive. Considerations made for D line have anyway general validity.

At the end of your work you talk about the savings on the annual health expense. A fact that generally is not taken into account, despite its importance. How does a network of subways influence on the welfare and the protection of the population?

A: In October the IARC, International Agency for Research on Cancer – part of the World Health Organization – included the waste products of combustion in diesel engine between carcinogenic of level 1, in other words those for which is certain the cause-and-effect connection. This is an unprecedented decision which has not been given the due importance: it is not difficult to imagine why.

The Danish Centre for Research on Cancer has followed for 13 years a population strewn all over Europe of 313 thousands of people (including also those followed by Italian researcher in Rome and Turin), identifying a clear relation between exposition to dust and lung tumour. In particular in the form which affects even non-smokers (adenocarcinoma). Researchers were able to correlate the 2.095 cases of lush cancer occurred in the period considered with the level of dust in the residence area of the patient, being able to correct the potential interfering effects as smoke, diet and kind of employment. For each increment of 5 μg for cubic meter of PM2.3 the risk of lung cancer increases by 18%, and of 22% for every increase of 10 μg for cubic meter of PM10. The more dust is fine, therefore, the most it is dangerous.

Again last year, an international team led by professor Mills from the University of Edinburgh confirmed another effect of urban pollution on admissions and cardio-circulatory deficit. By gathering data from 12 different countries, researchers were able to see a clear causal connection between the increase of the concentration of pollutant in the air and an instant worsen of the increase, even in the same day of the maximum exposure. The risk to end up in hospital because of an attack of heart failure or to die for this reason grows by 3.5% increasing of 1 part per million of carbon monoxide, by 2.3% for the increase of 10 part per billion of dioxide sulphur, by 1.7% for the same increase of nitrogen dioxide and of about the 2% for every increase of 10 μg for cubic meter of dust. Fine dust, passing from the lungs into the bloodstream, can be the reason of a generalized inflammation that facilitates the formation of atherosclerotic plaques, thrombi and ischemia. On the other hand, chemical stress determined by polluting particles affects also the autonomic nervous system (sympathetic and parasympathetic), causing arrhythmia and gradual damage to heart and coronary artery.

Other studies proved clearly the connection between pollution and respiratory disease (pulmonary, childhood asthma) besides neoplastic incidence (in particular leukemia ad myeloma) apart from genetic predisposition or personal behaviour. What is really surprising is the development of the diseases to the younger age groups and children.

M: Of course I support completely what Andrea says: it influences a lot. We need however to keep in mind that a system of mass public transport and his correct financial management does not solve suddenly the huge health problems and delays. It can, in any case, help and set an example on how to manage founds, and the simple idea of include in the calculation the coming negative externalities on health that could be avoided is scientifically very innovative. The investment strategies on health in the long run could absolutely include choices of this type. But we also know which lumps of influence we touch when we think of a rationalization of health costs. To state this way is the beginning of an, of course, very complex journey.

If they gave you the opportunity to realize only some of the lines that you supposed (probably for economical or political reasons), to which you would give priority? Or you would lose the network effect that makes this project something of necessary for Rome?

A: The Plan is conceived to be realized in sections, using part of the benefits produced little by little with the use of the new lines as a starting point to improve in the completion. As mentioned, D line is the most important in order to revamp the city. But it is even the one technically and economically more costly. In terms of containment and maximization of the effects, F line is the most interesting, with the transformation of the railway of Northern Rome, an infrastructure as strategic as underutilized. The F, running along Prati Fiscali street, could increase the productivity of branch B1 addressing the stream of one of the most populated quadrant of Rome.

Consider that from the 225 thousand passengers a day that originate from Montesacro and Nomentano, B1 line manages to capture 55 thousand of them. If the load would have been so, it would have been better to realize a tram to Piazza Bologna, without the need to resort to a subway.

M: The whole structure of the network is conceived to have the possibility of reuse existing infrastructure and build it by parts. To complete C line up to Ostiense is the first necessary step. Andrea dreams bigger than me, but I believe that this would represent an epochal change, as well as the resolution of a logistical and financial problem that risks to affect the city for decades. I guess that this is already much to hope for. If this idea, which appears simple, will impress the minds of those who administer, it may be possible to start on seriously discussing of the rest.

To sum up: is there a minimum glimmer that the idea becomes reality, or at least that this is the beginning of a serious discussion on the topic?

A: Rome MXL has been designed with the scientific method: our purpose was to start from a thesis, demonstrating his authenticity on the basis of a starting data series, with a path measurable, repeatable and controllable. To invest 1.000 euro in the right public transport creates a real and tangible similar of 1.175 euro: a minimum value equal to 175 euro of profit available for the city. For us it would count as a Nobel if the administration would utilize this approach to open the work of a Local Strategic Plan of Mass Transportation with clear and achievable objectives – because respectful of the 4S – in the next 5 years.

Traduzione a cura di Chiara Pino e Daniela De Angelis